BY JUMAI NWACHUKWU

ON October 1, 1960 as the Union Jack was lowered and the green-white-green colours was hoisted in a new air of freedom, Nigeria’s founding fathers saw education as a cornerstone of Indepemdence. Schools were to be the human factories of nationhood, producing doctors, engineers, teachers, and citizens with the skills to drive the new nation.

65 years later, the dream appears deferred. As the country marks her 65th Independence anniversary with the theme “Rebuilding Our Nation,” one sector stands at the heart of this rebuilding project: education. But what happens when the very attitudes that sustained the system are steeped in neglect, indifference, and shortcuts?

The story of Nigeria’s poor attitude toward education is not just about underfunded classrooms or striking lecturers. It is about a collective mindset that has allowed mediocrity, corruption, and misplaced priorities to dominate a sector meant to be the bedrock of progress.

Journey So Far: Education Standard In 65 Years

At independence, Nigeria inherited a relatively small but promising educational system. Mission schools dotted the landscape, while regional governments invested heavily in primary and secondary education. The Western Region’s free education policy under Chief Obafemi Awolowo in 1955 was a bold experiment that proved education could be a ladder for social mobility, while the 1970s oil boom brought hope of massive expansion, with universities springing up across the nation.

But as the economy faltered in the 1980s and military rule entrenched mismanagement, education began its long decline. From abandoned laboratories to overcrowded lecture halls, from the endless strikes of the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) to parents celebrating exam “miracle centers,” the rot grew deep.

Policies Without Follow-Through

At the heart of Nigeria’s education crisis lies governance. Despite numerous policy frameworks—such as the Universal Basic Education (UBE) program and various national education strategic plans implementation often falters. Bureaucratic inefficiencies, corruption, and underfunding mean schools lack essential infrastructure, learning materials, and qualified staff.

Experts argue that the government’s attitude towards education is largely reactive rather than proactive. Ministries of education, frequently plagued by political interference and short-term agendas, fail to create sustainable strategies. While policy documents may be well-intentioned, the absence of consistent monitoring, accountability, and long-term investment leaves schools under-equipped to deliver quality education.

Looking Bact At Neglect

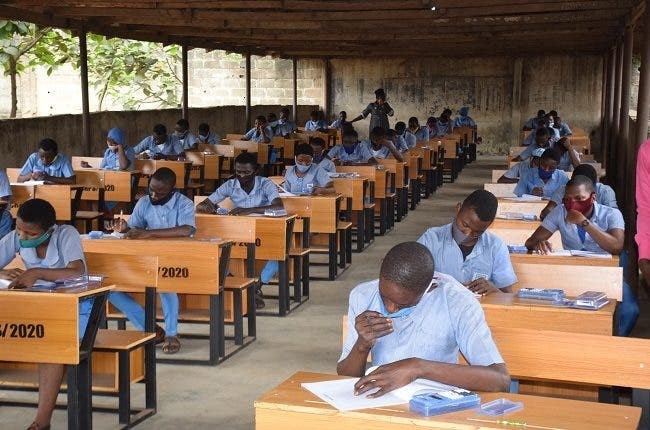

Perhaps the most glaring poor attitude toward education is governmental neglect. Budgets consistently short-change the sector, leaving schools without infrastructure, teachers underpaid, and research underfunded. For decades, education has been treated as an expense rather than an investment. Infrastructure tells the story: leaking roofs, broken chairs, chalkboards turned grey with age, and science laboratories without reagents. Where private schools mushroom with shiny uniforms and polished floors, public schools meant to serve the masses, are left to decay.

People were taught that teachers are the backbone of any education system, yet in Nigeria, they often bear the brunt of systemic neglect. Poor remuneration pushes many to take side jobs, reducing dedication to their craft. Some resort to absenteeism or extortion of students to survive.

A teacher in Delta State, Mrs Ifeoma Chukwudi, summed it up during an interview with The Pointer, she said, “How do you expect us to give our best when we cannot feed our families? Teaching has become charity work.” The poor attitude is not only financial, society itself often looks down on teachers, treating the profession as a last resort for those who could not “make it” elsewhere.

She further explained that in many classrooms, the hunger for knowledge has been replaced by the hunger for certificates. “Expo” (exam malpractice) is rampant, and miracle centers thrive during WAEC and NECO exams. University students often calculate how to “sort” lecturers rather than how to excel. Mrs Chukwudi noted that a third-year student of Political Science in one of the universities in Delta, told her bluntly during an argument that as a student, “Why stress yourself reading all night when you know the lecturer is waiting for you to drop something?”

“This normalization of shortcuts has eroded merit, leaving employers frustrated with graduates who lack basic skills”, she said.

According to her, most Parents also feed this cycle. Many are quick to bribe teachers to secure admission, examination success, or preferential treatment for their children.

Some openly encourage malpractice, reasoning that “everyone does it.” And the Society at large has embraced a dangerous attitude that glorifies quick money over honest learning. The child who cheats through exams but makes money in politics or entertainment is celebrated more than the diligent student struggling to make ends meet.

A father and a business man with two of his children in secondary school, Mr. Tunde Olufemi, also described the poor attitude towards the education system in Nigeria as a national tragedy: “When government officials send their children abroad while ignoring our public schools, it shows a lack of seriousness. If leaders cannot trust the system they supervise, why should ordinary Nigerians have faith in it?”

Also speaking was Mrs. Esther Umeh, a parent in Asaba, who said “What we see today is not the same quality of education we had years ago. Many public schools are in bad shape, and some parents even encourage malpractice just to help their children pass. It is a big shame.” She said.

Similarly, a retired teacher, Mrs. Roseline Ginika, shook her head in pains saying “We sacrificed our best years, but what did we get in return? Dilapidated classrooms and a generation that does not respect hard work.”

Politicians who pledge reforms often send their children abroad or to expensive private institutions, leaving the masses trapped in failing public schools. This hypocrisy has deepened inequality and removed accountability. She added that the decline of education in Nigeria is not the fault of any single group, but that it is the cumulative effect of attitudes across all stakeholders.

A government that fails to invest, parents who neglect their supervisory role, teachers who lack motivation, and students who disengage create a vicious cycle. Each party’s attitude reinforces the others, resulting in systemic decay.

Mrs. Ginika also noted that parents play a critical role in shaping the educational outcomes of their children, yet in Nigeria, parental engagement is inconsistent. For many, education is seen as a box to tick rather than a lifelong investment. Economic pressures lead some parents to prioritize immediate income over schooling, resulting in irregular attendance or dropping children from school entirely.

Furthermore, parents often abdicate responsibility for their children’s learning to teachers, failing to monitor progress or provide necessary support at home. This lack of involvement fosters a culture where education is undervalued, and children mirror these attitudes, perceiving learning as optional rather than essential.

Call To Action

As Nigeria reflects at 65, rebuilding must begin with a mind-set shift. Poor attitudes cannot be legislated away; they must be consciously unlearned. Nigeria must treat education as infrastructure. Just as roads and bridges are built with seriousness, so must schools, laboratories, and teacher training be prioritized.

Transparent funding and implementation are key. Attitude toward teachers must change. They deserve not only better pay but also respect and support. Strict measures against exam malpractice should be enshrined and virtues, as honesty and hard work should once again be rewarded in the school system. Also exam malpractice must be fought with both enforcement and cultural change. Students must be re-taught that hard work pays and parents advised to instil discipline, encourage hard work, and avoid sponsoring malpractice.

Politicians and public officials should enrol their children in Nigerian public schools to experience the system first-hand so they can be compelled to improve it.

Towards Sectoral Rebirth @ 65

Rebuilding Nigeria is impossible without rebuilding education. The poor attitudes that have crippled the system are a mirror of the wider national psyche a culture of shortcuts, neglect, and misplaced values, so as the country celebrates 65 years of independence, the green-white-green should remind us not only of past struggles but also of future possibilities.

A nation that invests in education invests in its survival. The challenge is clear: Will Nigeria continue to treat education with indifference, or will it embrace a new attitude that values knowledge, integrity, and innovation? At 65, the choice is stark. To rebuild our nation, we must first rebuild the classrooms where tomorrow’s leaders are formed. Anything less is a betrayal of independence itself.