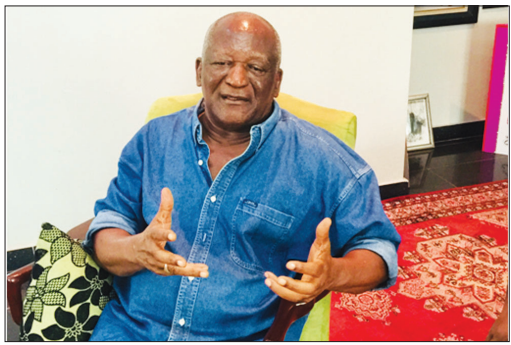

BY NEWTON JIBUNOH

THIS reflection unfolds in three parts, each drawing from the voices of those who have shared in my journey, offering layered insights into the continuing search for identity, legacy, and purpose.

Family and friends have started the countdown to my eighty-eighth birthday. The reminders come with warmth, sometimes with laughter, but always with a certain reverence as if each mention of my age carries a deeper meaning. As the day approaches, I find myself, more than ever, turning inward. Not simply reflecting on the years gone by, but engaging in a quiet, personal excavation of memory, purpose, and identity. My birthdays over the years have become sacred rituals of introspection. I have never been drawn to noise or grand celebration. Instead, they offer me a recurring opportunity to withdraw to think not just about my own life, but about life itself: about nature, about the earth beneath us and the sky above, about the waters that flow endlessly, and the deserts that remain vast, open, and strangely comforting in their emptiness.

Among all the natural wonders that have captured my imagination, none have held me quite like the Sahara Desert and the vastness of outer space. Both speak in silence, one through endless stretches of golden sand, the other through infinite blackness pierced by distant stars. Untouched, unclaimed, yet full of presence. There’s a peculiar truth buried in that silence: the truth of insignificance and the potential of self-awareness. The desert does not shout. It simply is. And in its vast stillness, one is forced to confront oneself.

It brings to mind Shakespeare’s words: “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players; they have their exits and their entrances; and one man in his time plays many parts.” In the presence of such vastness, the stage feels fleeting, the roles momentary. Yet it is in this realization that we begin to grasp the value of each act, each breath and each moment of being.

Over the course of my life, I have been privileged to witness the world from many unique vantage points. I have fished in mighty rivers and open oceans, walked and hunted in ancient forests, and stood beneath trees that have seen centuries pass. I have flown aboard the Concorde, soaring fifty-five thousand feet above the earth’s surface, looking down at our planet’s curvature, the way the clouds folded around it like a thin veil. It was humbling. From that height, you realize how small our individual footprints are, and how much of the world exists entirely without our interference. These experiences were not just adventures; they were revelations. They peeled back the layers of distraction and reminded me of the question that has quietly followed me through life: Who am I, really?

Years ago, in this same column, I penned a piece titled “Don’t You Know Who I Am?” Reflecting on my journey and the pursuit of power, I acknowledge the prevalent Nigerian phrase, “Don’t you know who I am?” This phrase often signifies a hunger for power, a desire to assert oneself. In the prologue of my book, “Hunger for Power,” I delve into the notion that understanding power is central to my quest, recognizing that many who use such phrases lack self-awareness. It wasn’t written from a place of arrogance, but rather from a deep yearning. I wanted people to consider the selves they had buried under duty, ambition, fear, and routine. I wanted to spark a conversation about identity not the one given to us by others, but the one we discover in solitude, in quiet, and in communion with something greater than ourselves.

For over half a century, I have engaged in a profound exploration of self, grappling with questions of human existence and purpose. Why was I created as a human? What am I meant to do, to take, and to give back? It’s a journey that began 87years ago, departing my mother’s womb for life on planet Earth, the only known abode of life in the vast universe. This relentless pursuit has driven me through diverse experiences. At the age of 27, I set out on a solitary expedition, driving from London through Europe, crossing the Mediterranean, and journeying across the vast Sahara Desert to Nigeria. That experience awakened in me a deeper sense of responsibility, eventually leading me to seek accreditation with the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. Nearly four decades ago, driven by a passion for preserving Africa’s rich history and cultural legacy, I attempted to establish a private museum in Lagos.

My commitment to honoring African icons later inspired the creation of a monument in tribute to Nelson Mandela, motivated by the United Nations’ declaration that the world would be a better place if more people lived by Mandela’s values. And yet, despite these milestones, I find myself still on a journey; a journey inward. I continue to search for a deeper understanding of who I am. Alongside family, friends, co-writers, and loyal readers of my weekly column, I seek clarity not only about my identity, but also about the purpose that shapes my existence.

In this reflection, I draw on the perspectives of those who have walked closely with me; family, friends, and longtime associates whose insights continue to shape and enrich my ongoing journey of self-discovery, Mycousin, Mr. Onuorah Aligbe whom I have known for half a century, wrote from Atlanta Georgia in response to my earlier article titled “Don’t You Know Who I Am?” offering reflections that helped deepen the questions I continue to explore today; he stated;

Dr. Newton C. Jibunoh is my Uncle. By DNA, he is actually my Cousin, once removed. He is mymother’scousin, but because my mother hadnomaternalbrother, my mother saw him as a younger brother and so I earned the right to call him my uncle. He always introduced me to his guests and friends first as his colleague and his former Deputy Managing Director when he was the Chairman/CEO of Costain (West Africa) Plc. The ease with which he would say it belies the simplicity with which he achieved that transformation of my person.

The first time I met my Uncle was in 1967 when he drove home to our hometown in his 1500cc Volkswagen saloon car of the famous Sahara crossing. I was eleven years old then but the historical drive across the Sahara had been top news in my secondary school, so I was aware of it. At home my Grandma who was never an extrovert, was ecstatic that the nephew whom she considered a son was home after his studies in England. I got introduced to him, he ruffled my hair, and that was it. I had a big story to tell in school.

Twelve years later, I met him for the second time when I went to him in search of a job at the end of my national service. In place of a job, he sent me off on his scholarship to get a master’s degree. At the end of my course, he helped to secure a job for me in an engineering firm. Six years later he invited me to join him in Costain (West Africa) Plc, as a Senior Engineer. With time, and being a member of the team of management in three companies where he held directorship positions I found him to be a firm apostle of the indigenization policies of the Federal Government in the last three decades of the 20thCentury.InCWA, the management employed qualified Nigerian professionals and specialist subcontractors in the execution of our contracts, ensuring that the quality of the completed projects and delivery times were not compromised. To make sure they were well rounded, engineers and managers were routinely sent to Costain in the UK for specific trainings and developments.

Initially, most clients were skeptical but after inspecting completed projects which we willingly gave them tours of, they went along with us by awarding us the contracts we sought. Such was his belief in the capabilities of our home-grown professionals that many times he defended the use of local personnel in our projects even over the threats of losing the contracts. Other times Employers would demand that he provide his guarantees for our performance, often in addition to company guarantees already in place, and he willingly would comply using his personal properties or holdings as collaterals. This was only known to the top management. I marveled at these, seeing how committed he was, and seeing how workers would sometimes deliberately want to drag out a project completion schedule over inconsequential demands that could be solved through negotiations.