BY JUMAI NWACHUKWU/CHIKA KWAMBA/OGORAMAKA AMOS/RITA OYIBOKA

Recently, the Delta State Police Command, in a post made on social media, threatened to clamp down on those indecently dressed, warning that an N50, 000 sanction would be imposed on supposed offenders. Expectedly, the development sparked a public reaction, beginning with the state government.

According to a statement by the Ministry of Justice, ‘’The Ministry of Justice wishes to categorically state that while the Violence Against Persons Law, 2020 criminalises certain acts that may be categorised as indecent exposure of private parts, it is essential to emphasise that the interpretation and application of the Law rests exclusively with a Court of law. No security operative has the power to impose any punishment on any individual without due process of law.

‘’The Ministry of Justice also wishes to state that the use of the phrase “indecent dressing” instead of “indecent exposure” as provided in section 29 of the VAAP law raises concerns about potential human rights violations. ‘’For the avoidance of doubt, no provision of the VAAP Law authorises law enforcement agents to harass, arrest, or punish citizens based on their dress or appearance. Any such action must follow proper legal procedures and be founded on lawful complaints or charges brought before a competent court of law.

‘’The Ministry of Justice calls on all security agencies to exercise restraint and professionalism in the discharge of their duties and to respect the constitutional rights of all citizens. We also urge the public to report any incidents of abuse to the Office of the Public Defender in the Ministry of Justice’’.

Reacting to the issue of indecent dressing, a secondary school teacher at Holywood International School Mrs Chioma Ahanonye told The Pointer that one of the main challenges is the increasing influence of social media and popular culture, which often promotes fashion choices that conflict with school standards.

Ahanonye noted that many students come to school dressed inappropriately, either too casually or in attire that draws undue attention, creating distractions in the learning environment. Another challenge, according to her, is the pushback from students and sometimes parents, who view dress regulations as overly strict or outdated.

She emphasized that acceptable dress standards are usually defined in the school’s code of conduct, which is shared with students and parents at the beginning of the school year. ‘’These standards are based on values such as modesty, neatness, safety, and cultural sensitivity. Enforcement involves routine checks by staff and private conversations with students who violate the dress code. Consistency and fairness are key in ensuring that all students are held to the same expectations without bias.

Mrs Ahanonye added that strict dress codes can contribute to a more disciplined environment by reducing distractions and promoting a sense of order. ‘’However, their impact on morality is less direct. Morality is better shaped by character education, mentorship, and positive role modelling. Dress codes should support a respectful environment, but not be the sole tool used to build moral values.

She reiterated that Education is always the better path. “Instead of punishment or shaming, we encourage respectful dialogue, helping students understand the reasons behind the dress code. Engaging parents in discussions and organizing sessions on personal grooming, self-worth, and cultural appropriateness can be more effective.“

“We face the typical challenges of adolescence, where students are eager for acceptance and attention, especially from the opposite sex. This often influences their choice to dress in ways that are considered indecent or inappropriate for the school environment” she said

Meanwhile, the Senior Special Assistant to the Governor on Moral and Diaspora Affairs, Dr Favour Obakoro, called for empathy and strategic thinking in addressing the issue of indecent dressing and related social behaviours among youths. “Before you try to correct or judge someone, understand them. Real change begins with empathy, not condemnation,” she said.

Obakoro stressed that government policies, particularly those targeting moral conduct, must be implemented with wisdom and caution. “If the government wants to enforce policies like that, they need the right people, whether in government or not, and the right agencies to carry out the work. “You can’t just send in the police. Who knows which officers will be involved? They could end up harassing people and creating more chaos. You cannot use the devil to fight the devil. It’s not possible,” she explained.

According to her, the starting point should always be dialogue and planning. “The first step should be dialogue. Sit down and ask, what was the intention behind it? Intentions matter. What were you thinking when you came up with this idea of tackling indecent dressing?”

Drawing from personal experience, she shared a candid account of her past and transformation. “I used to wear revealing clothes, a lot. But one day, I looked at myself, saw where I was going, and decided to change. Nobody told me. I corrected myself. “That’s the best advice anyone can receive, the one you give yourself, in your quiet moment. No advice from outside will work until you sit alone, reflect on your past, your present, and your future, and call yourself to order,” she revealed. She added that her story should serve as motivation for young girls facing similar challenges. “That, in itself, is a testimony, proof for every young girl that they can be better. Don’t criticise or mock them. Don’t go shouting. That approach will never work. Instead, share your story. Let them know why they should choose a better path.”

Dr. Obakoro emphasised that sustainable solutions must be driven by proper awareness and inclusive engagement. “So, the right way forward is getting the right people to handle such initiatives. Before rolling out any policy, start with awareness. Host workshops. Run seminars. Produce skits and short films. Use creative platforms. That’s the best way to engage youths. You can’t just act without groundwork, that’s where we keep failing.”

She also proposed a creative and youth-friendly approach even within law enforcement structures. “Even the police should have an entertainment unit, using jingles and fun programmes to communicate messages. “There must be awareness campaigns. And those handling it shouldn’t be chosen simply because they’re pastors. Dressing decently isn’t exclusive to religious people,” Obakoro affirmed.

The Governor’s aide further reiterated the goal of true transformation. “In the end, the goal should be genuine transformation, not harassment. We must change hearts, not just appearances,” she remarked.

Meanwhile, real estate developer Mr Emmanuel Orumgbe stressed that true solutions to societal decay lie not merely in moral enforcement but in economic empowerment and systemic reforms.

He faulted the inconsistency in the government’s approach to social control and law enforcement. “In one breath, the state government says they do not have control over the police to ensure the safety and security of citizens. “In another, they are announcing crackdowns on indecent dressing. How can you enforce a moral standard when basic safety and economic stability are not guaranteed?” he asked.

Mr Orumgbe argued that the root of many social vices lies in the worsening economic situation in the country. “The government needs to create an enabling environment that drives economic growth and job creation, especially for young people.

“When people are gainfully employed and can see a clear future, they will not resort to crime, prostitution, or internet fraud. These vices will disappear like smoke in thin air.” He also warned that superficial interventions like dress codes without broader social investments could do more harm than good. “You can’t expect young people to behave ‘morally’ when they are hungry, idle, and hopeless. It’s unrealistic. Let’s focus on building a society that gives people real options,” he added.

Meanwhile, a longtime resident of Asaba, Mr Raymond Egbunu, supported the government’s plan to address indecent dressing, especially among teenage girls.

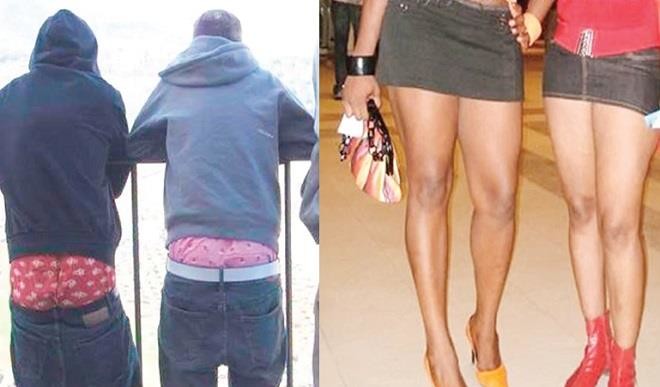

“I think it’s a welcome move. When I lived in Warri, what some girls between the ages of 12 and 18 wore in public was alarming. They would parade the streets wearing barely-there outfits, completely unbothered. It was as if decency had lost all meaning,” he said.

He noted that similar trends are beginning to creep into Asaba, raising concern among older residents. “These young girls want to turn Asaba into another version of the chaos we once saw in other urban centres. It’s not just about what they wear, it’s the boldness, the attitude, and the sense of entitlement to behave any way without consequence. That’s why I believe government intervention is necessary.”

However, Mr Egbunu was quick to add that enforcement must be handled sensitively and responsibly. “This should not be an avenue for harassment or police brutality. Sensitisation is very important. There must be public enlightenment. You can’t just send officers into the streets without clear guidelines. Otherwise, it’ll lead to chaos and abuse of power.” He also suggested that the approach should be holistic. “They should engage parents, community leaders, schools, and even churches and mosques. This is a moral conversation, yes, but also a societal one. Everyone has a role to play.”

Port Harcourt, the capital of Rivers State, is a city where tradition and modernity intersect. Among the numerous social disputes forming its urban culture, the subject of “indecent dressing” has also aroused controversy. While some say that dressing is a question of personal liberty, others believe that public decency must be maintained. But where does the law stand?

Barr Joseph Wonda, a lawyer based in Port Harcourt says “The Nigerian Constitution, particularly the 1999 version as amended, doesn’t come right out and talk about how people should or shouldn’t dress. But it does lay down the principles that affect this conversation in real and practical ways. “Take Section 38, for instance—it guarantees every Nigerian the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. Now, that may not sound like it’s talking about clothes, but when you think about it, it is. If someone chooses to wear a hijab, a cassock, or even traditional religious garments, that’s often a reflection of their belief system. And the Constitution protects that”. ‘’So, when people talk about regulating dressing, especially in a religious or cultural context, we have to be careful not to cross into territory that violates that freedom. That section is a strong shield for people who choose to dress in ways that express their faith or identity, that’s if we want to look at things from that angle”. “When we talk about rights in the Nigerian Constitution, we must also talk about their limits. Section 45 is very clear—it allows the government to place restrictions on certain rights if it’s in the interest of public safety, order, morality, or public health. So yes, in theory, this could support the idea of enforcing a dress code in public institutions or spaces, especially if it’s genuinely aimed at protecting what society considers moral standards. ‘’Now the same Constitution also protects the dignity of individuals. Section 34 speaks about the right to dignity—it says no one should be subjected to inhuman or degrading treatment. So, if enforcing a dress code crosses the line—say, by harassing or humiliating someone for what they wear—that enforcement could become unconstitutional. ‘’At the end of the day, the Constitution tries to balance personal freedom with societal values. The real issue is how these laws are interpreted and enforced. It’s a delicate balance’’ he said.

Evelyn Eze, a constitutional lawyer practising in Rivers State, begins by pointing to Section 37 of the 1999 Constitution (as amended), which guarantees the right to privacy, family life, home and correspondence.

“The right to privacy includes personal autonomy over one’s body and appearance,” Eze explains. “While society can express disapproval, the Constitution does not empower public institutions to regulate how citizens dress unless such dressing directly threatens public order or violates an existing law.”

Eze also references Section 38, which guarantees freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. In practice, this means individuals have the right to dress according to their religious or philosophical beliefs, as long as such expression does not conflict with public safety or morality in a criminal context.

Another respondent, Emeka Okoro, a practising lawyer in Port Harcourt, explains: “There’s a common misconception around the legality of so-called ‘indecent dressing’ in Nigeria,” he begins.

“Now, Section 26 of the Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act — commonly called the VAPP Act — talks about indecent exposure, but not in the way many people think. The law only criminalises the deliberate exposure of one’s genitals to cause distress or to lure someone into an act of violence or sexual activity. That kind of behaviour attracts a penalty of up to one-year imprisonment, a ₦500,000 fine, or both. “Beyond that, we have to understand that what some people call ‘indecent dressing’ — like wearing revealing clothes — is not in itself a crime under Nigerian federal law. “Yes, under Sharia Law, which is enforced in 12 northern states such as Zamfara, Kano, and Sokoto, there are strict codes of dressing, particularly for women. But this law applies only to Muslims. Non-Muslims are not bound by it unless they willingly choose to submit to its rules, which is very rare. “So if we’re speaking about Port Harcourt, or any part of Southern Nigeria really, there’s no existing legal framework that criminalises what is loosely referred to as ‘indecent dressing’.

“That’s why it is both unconstitutional and unlawful for law enforcement officers to arrest, detain, or harass anyone based solely on what they’re wearing. Doing so violates the person’s fundamental human rights as guaranteed by the Nigerian Constitution. Everyone has the right to personal liberty and dignity, and that includes freedom of expression even in how one chooses to dress.”

A Port Harcourt-based activist, Mr. Henry Binabo, explained that while there’s no nationwide law directly banning indecent dressing, some states have enacted laws around public decency. “You’ll find examples in places like Lagos or Kano, where there are specific laws aimed at regulating how people dress in public spaces,” he said.

He added that beyond state laws, institutions also have the authority to enforce dress codes. “Universities, for instance, operate under their administrative powers, so they’re able to decide what is acceptable within their campuses. The same goes for the courts and some government buildings.”

Citing an example, he pointed to the University of Port Harcourt (UNIPORT). “UNIPORT has a pretty strict dress code. You can’t just walk into a lecture hall wearing something they consider inappropriate – like overly revealing clothes or sagging trousers. It’s all part of their internal effort to promote discipline and a sense of decency among students,” he said.

Also, Sam Jaja, a constitutional lawyer based in Port Harcourt, explains that while public institutions are allowed to set dress codes as part of their internal regulations, these rules must not conflict with citizens’ constitutional rights.

“Institutional policies are fine—as long as they don’t violate fundamental rights,” he says. “For instance, denying someone access to education or a public service simply because of how they’re dressed could be legally challenged under Section 42 of the Nigerian Constitution, which protects against discrimination.”

He adds that the courts have often upheld dress codes when they’re linked to maintaining order or a professional image. “A bank, for example, can insist that staff dress formally because it aligns with their corporate identity. But that’s different from, say, a hospital refusing to treat someone in an emergency just because of their clothes—that would be both unethical and unconstitutional.”

Jaja, warns: “Many ‘indecent dressing’ laws are vague and prone to abuse. A woman in a short skirt may be harassed, while a man in shorts faces no consequences. Such double standards violate equality under Section 42.” He also expresses deep concern over moral policing through vague indecency laws. “We see, time and time again, how women in short skirts or sleeveless tops are harassed while men in similar or even more revealing attire walk by without incident. This points to a double standard that violates the principle of equality as guaranteed under Section 42 of the Nigerian Constitution,” he adds.

Section 42 explicitly prohibits discrimination based on sex, among other factors. For Jaja, these dress code enforcements are not just arbitrary — they often reflect deeper gender biases entrenched in society and law enforcement. He continues: “Beyond discrimination, we must also ask: what public harm is being prevented? If there’s no threat to safety or public order, then denying someone access to education, healthcare, or justice based on their clothing becomes not only unjust but unconstitutional.”

Jaja also warns about the legal and psychological consequences of such policies. “It breeds fear, humiliation, and even violence. Imagine a young woman being dragged out of a lecture hall or courthouse because of her blouse. That’s not morality — that’s institutionalised shaming.”

He calls for clearer legal definitions and public education on rights: “If dress codes must exist in institutions, they need to be written in clear, objective terms and applied equally to all genders. More importantly, citizens should be aware of their rights and know when such enforcement steps into the realm of abuse.” Ultimately, Jaja concludes with a call to balance: “We can uphold public decency without trampling on dignity. The law should protect, not police appearances.”

Emeka Okoro, a Port Harcourt-based legal practitioner says “What is considered decent in Lagos might be frowned upon in Kano,” he explains. “Nigeria is a melting pot of cultures, religions, and values, and we must be careful not to let personal or regional standards morph into nationwide legal mandates.” He refers to Section 45 of the 1999 Constitution (as amended), which permits the government to place limitations on certain fundamental rights — including freedom of expression and movement — in the interest of public safety, order, morality, or health. “This section gives the state some latitude to legislate on sensitive issues like public nudity or acts considered obscene,” he says. “But there’s a difference between cultural expectations and legal enforceability.”

Okoro is quick to clarify that modesty in dressing, while often promoted by communities and religious groups, does not automatically amount to a legal obligation. “Unless a person’s attire violates existing laws—like those prohibiting indecent exposure or causing public nuisance—the law does not give room for punishment based on how someone chooses to dress,” he adds.

He cites Section 26 of the Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act (VAPP), which criminalises the intentional exposure of genitals with the aim of distressing others or soliciting sexual activity.

However, he points out that the law is targeted at specific acts of sexual harassment, not general appearance or fashion. “We must separate moral judgment from legal standards. People have the right to dress in a way that expresses who they are, provided they don’t infringe on the rights or safety of others,” he says.

Okoro further cautions against arbitrary arrests or harassment in the name of enforcing ‘public decency,’ warning that such actions could themselves violate the constitutional right to dignity under Section 34.

“Using force or shaming individuals over clothing choices can become a form of inhuman or degrading treatment,” she notes. “And that is unconstitutional’’ even as she urged policymakers to adopt a rights-based approach when addressing public morality. “The law should protect dignity and safety.”