THE recent decision by the Federal Government to prohibit direct admission or transfer of students into Senior Secondary School Three (SS3) marks a significant intervention in Nigeria’s secondary education system. The policy, announced by the Ministry of Education, Mr. Tunji and scheduled to take effect from the 2026/2027 academic session, is clearly aimed at tackling the deepening culture of examination malpractice, particularly the proliferation of so-called “special centres” that have turned public examinations into commercial ventures.

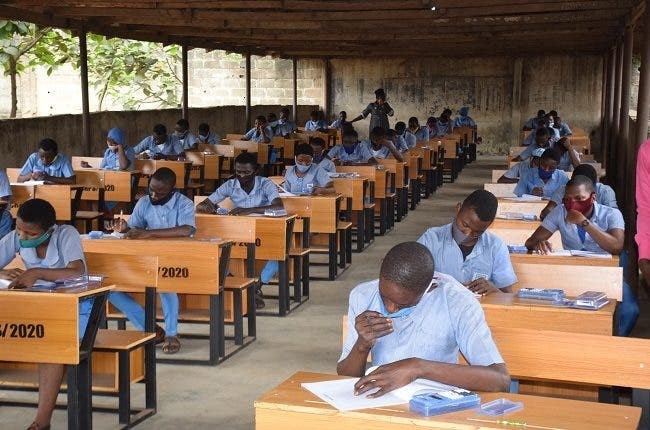

For years, the Senior School Certificate Examination has been undermined by the practice of moving students into selected schools shortly before examinations, not for academic reasons but for guaranteed “assistance” during exams. These centres, often registered as legitimate examination venues by bodies such as the West African Examinations Council (WAEC), the National Examinations Council (NECO) and the National Business and Technical Examinations Board (NABTEB), have become havens for cheating, eroding the credibility of certificates that serve as a gateway into tertiary education.

By barring admissions and transfers into SS3, the government seeks to cut off this last-minute manoeuvring that prioritises shortcuts over learning. The logic behind the policy is sound. Senior secondary education is designed as a three-year continuum, with SS1 and SS2 laying the academic foundation for the final year. Allowing students to suddenly appear in SS3 disrupts academic continuity and makes meaningful assessment and monitoring almost impossible.

More importantly, it incentivises malpractice, as schools and parents alike treat SS3 as an examination staging post rather than the culmination of structured learning. Restricting admissions strictly to SS1 and SS2 reinforces the idea that education is a process, not a transaction.

However, while we laud the policy, we fear that its success will depend largely on enforcement. Nigeria has no shortage of well-crafted education policies that fail at the point of implementation. Many of the “special centres” that the government now seeks to curb operate with the tacit approval or protection of powerful interests.

Some proprietors enjoy political cover, while others exploit regulatory loopholes to continue business as usual. If the authorities merely issue directives without following through with sanctions, the policy risks becoming another paper tiger. Violations must attract swift and visible consequences, regardless of whose interests are threatened. Anything less would amount to preaching virtue while practising vice.

Clarity is another crucial issue. While the directive states that no admission or transfer into SS3 will be permitted under any circumstances, real-life situations often test the rigidity of such rules. Families of service personnel, including members of the armed forces, paramilitary agencies and other professions that require frequent postings across the country, could be unfairly affected. It would be unreasonable to force families to fragment or deny children continuity of education because of circumstances beyond their control. The policy must therefore clearly outline exemptions or special provisions for such cases, without opening the floodgates to abuse. A well-defined framework for genuine transfers, backed by strict verification, is necessary to ensure fairness.

Beyond government action, there is also a moral dimension that cannot be ignored. It is deeply troubling that many parents knowingly enrol their children into these special centres, effectively buying success instead of encouraging diligence and integrity. In doing so, they undermine not only the education system but also the values they ought to instill in their children. Examination malpractice does not begin in the examination hall; it begins with the willingness to cut corners and normalise dishonesty. This culture has far-reaching consequences, producing graduates who lack competence and confidence, and feeding a wider societal crisis of integrity.

The prohibition of direct SS3 admissions, if properly enforced, could help reverse this trend. When parents and students realise that shortcuts are no longer available and that offenders are being punished, attitudes may begin to change. Hard work, consistency and genuine learning could once again become the pathways to academic success. Over time, this would restore confidence in public examinations and ensure that certificates truly reflect ability.

Ultimately, this policy is a step in the right direction, but it must be matched with political will, institutional courage and moral consistency. Only then can the prohibition of direct admission into SS3 achieve its intended purpose of promoting academic integrity and deserved excellence in Nigeria’s education system.