BY VICTORY OKONJO

It seems like every few years, a new trading platform emerges in Nigeria that appears promising during launch, but quickly takes a drastic turn, ripping many Nigerian off their hard earned money and leaving a thick atmosphere of regret in its trails. The infamous Crypto Bridge Exchange platform (CBEX) despite not holding any official licensing as a regulated investment platform, managed to gain significant popularity among investors seeking high-yield opportunities in the digital finance space, leveraging aggressive marketing strategies to attract users.

Marketed as an AI-driven trading system, CBEX assured investors of guaranteed returns, sometimes as high as 100% in just 30 days. With sleek branding and aggressive social media campaigns, the platform managed to gained plenty traction on short notice, attracting thousands of users eager to capitalize on the booming crypto market. Influencers and promoters amplified its appeal, showcasing supposed success stories and lavish lifestyles funded by CBEX investments. For months, withdrawals were processed smoothly, reinforcing the illusion of legitimacy.

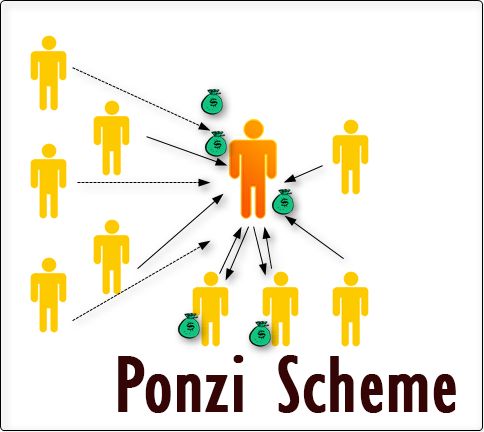

However, the bitter reality with Ponzi schemes such as these is that the cracks must begin to show whenever withdrawal requests start to outpace the incoming deposits. What investors did not take into cognizance at the time was that beneath its polished exterior, the platform operated without any proper regulatory oversight, inadvertently setting the stage for its inevitable downfall. By April 2025, CBEX abruptly shut down, wiping out investor funds and leaving them stranded and brutalized, financially and emotionally.

When asked to shed light on the situation, a veteran crypto trader, Nnaemeka Udoji attributed the general appeal of Ponzi schemes to the prevailing economic environment, citing high inflation, widespread unemployment and a growing distrust in traditional financial institutions from the citizens. He said, “Whenever we want to understand why these tragic incidents keep happening, we have to take a step back and look at the country’s economic structure right now. What percentage of the population is even earning the so-called minimum wage? Poverty is rampant in the country right now, and poverty breeds greed.”

“Everybody is desperate right now to make money. The ones who are not wicked enough to start doing money rituals or kidnapping people, will look at opportunities like this as a form of quick cash out. Who doesn’t like easy money?”

A young POS operator named Gift Dike was unfortunate enough to fall prey to the CBEX schemes. She said, “I found out about CBEX from a Telegram group chat. I did a little research and the evidence I saw convinced me to give it a try. I put in N100,000 from my business money and was planning to use the returns to open a location to start a saloon. I had already paid six months’ rent on the new space when CBEX disappeared. Honestly, I don’t like to remember it happened. I don’t know what is worse between the shame or the financial loss.”

“One of my friends invested around N200,000 just three weeks earlier and his balance multiplied over N330,000. He’s one of the reasons I even wanted to try out this business. He went and borrowed N600,000 from cooperative before the platform shut down. His wife still doesn’t know that he borrowed money from cooperative.”

THE LEOPARD NEVER CHANGES ITS’ SPOTS

CBEX operated using the classic Ponzi structure disguised as an advanced trading platform, promoting a business model believed to utilize artificial intelligence algorithms to identify profitable cryptocurrency trading opportunities. Financial analyst, Vincent Ijeh pointed out the obvious fallacy in this structure. According to him, “any business model that promises returns of up 100% within just 30 days is already a big red flag because it is mathematically impossible in a legitimate trading environment. Sustainable investment returns are supposed to range between 5-15% for an entire year. So it is funny when businesses like CBEX come and start talking about triple-digit yields within the span of a single month. That’s an abuse of financial logic and an obvious lie.”

In addition to this, the platform’s operational mechanics were deceptively simple. Early investors received their promised returns funded entirely by deposits from newer participants rather than actual trading profits. This was only possible because CBEX had succeeded in creating an illusion of legitimacy by processing withdrawals promptly during its growth phase while showcasing a sophisticated trading interface that displayed fictional trading activities. Ijeh alluded to this when he noted that, “one of the most effective ways that these fraudulent business draw victims in is by confusing people with complex trading charts abd AI analysis reports. Gullible fellows will think those reports are original or professional.”

When it comes to schemes like CBEX, investor demographics often span across various socioeconomic backgrounds, albeit particularly centered around three primary groups. The first segment comprised of the young, tech-savvy Nigerians who view the platform as their ticket to the global digital economy. The second group includes the middle-class professionals investing retirement funds or family savings. The third category are older, less tech-savvy individuals who are entirely reliant on testimonials from trusted community members.

Ignorance they say, is not an excuse. Economic desperation brought about by high cost of living and depreciating naira, in tandem with financial illiteracy among most members of the public will always produce unfortunate victims for these criminal entities. Ponzi operators capitalize on this ignorance, exploitung people’s desperation for financial security. In some cases, however, the victim might be fully aware of the risks involved but will choose to indulge anyway because they believe there truly is a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Ijeh noted that not all investors engage with these platforms in good faith themselves. He asserted that some of these investors might already aware that the platform is a sham, but knowingly participate anyway, hoping to exit before the inevitable collapse. He went ahead to share a revealing anecdote: “During the 2016 MMM saga, a close female friend I knew was gushing about an investment opportunity that she recently discovered. I recall telling her back then, ‘this is a Ponzi scheme.’ Funnily enough she did not argue that with me. She accepted that it is a Ponzi schemes but will still play her cards anyway because according to her, it’s better than not taking any action. So the truth is that some victims of Ponzi schemes might be fully aware of the risks but choose to approach it like a gamble, similar to betting platforms for instance.”

Critics have also argued that apart from being a big gamble, investors will often get the short end of the stick because these schemes are just as exploitative as they are risky. A report from BusinessDay highlights how platforms like CBEX and MBA Forex leverage social media to create an illusion of legitimacy, ultimately leading to billions in losses. According to the report, “Nigeria’s economic struggles — high inflation (24.23% as of March 2025), stagnant wages, and unemployment — have created fertile ground for fraudulent schemes. Platforms like CBEX, MBA Forex, and Binomo lure desperate Nigerians with promises of unrealistic returns, often exploiting the growing interest in cryptocurrency and forex trading.”

A TIMELINE OF FALSE PROMISES

Nigeria’s journey with Ponzi schemes began in the late 1980s to early 1990s during the Structural Adjustment Program era, when economic hardship created fertile ground for dubious investment opportunities. The first widely documented scheme was the “Planwell” scandal of 1991, which promised 30% monthly returns and collapsed after collecting millions from civil servants and middle-class Nigerians. A pattern was established that would repeat itself for decades to come: economic distress creating vulnerability to unrealistic promises of financial salvation.

The early 2000s witnessed the emergence of more sophisticated operations as Nigeria’s internet connectivity expanded. Wonder Banks like Nospecto Oil and Gas (2002) and Pennywise Investment (2004) operated under the guise of legitimate businesses while offering returns of up to 40% bi-monthly. The most notorious of this era was the Umana Umana Investment scheme, which devastated communities in South Eastern Nigeria by collecting over ₦100 million before its promoters vanished. In a bittersweet ending however, it ultimately led to the arrest of the scheme’s progenitor, the former Minister of Nigeria Delta Affairs, Dr. Umana Okon Umana in 2020.

The true watershed moment came in 2016 with MMM Nigeria, which represented a quantum leap in scale and sophistication. Promising 30% monthly returns through a “mutual aid” structure rather than traditional investments, MMM leveraged social media and digital payment systems to reach unprecedented numbers of participant — estimated at over three million Nigerians. When it collapsed in December 2016 after a one-month “system pause,” the financial devastation was estimated at ₦18 billion. MMM’s temporary success inspired numerous copycat operations like Ultimate Cycler, GetHelp, and Twinkas, which collectively extracted billions more from desperate Nigerians.

The cryptocurrency boom of 2017-2020 ushered in the next generation of investment frauds, which blended legitimate blockchain technology with fraudulent business models. Operations like Bitcoin Wallet (2019) and Paxful Trading Investment (2020) exploited Nigerians’ growing interest in cryptocurrency while their limited understanding of the technology created perfect conditions for deception. These schemes distinguished themselves by targeting tech-savvy youth rather than traditional victims, positioning themselves as revolutionary financial innovations rather than mere investments.

The biggest factor that distinguishes modern schemes from previous ones is their integration of legitimate financial technology elements with fraudulent operations, creating unprecedented challenges for regulators and victims alike. Throughout this evolution, the psychological drivers have remained remarkably consistent: economic desperation, distrust of traditional institutions, and the persistent hope that financial miracles might provide escape from systemic economic constraints. This hope, or rather blind faith, emerges as perhaps the most powerful psychological driver behind participation in Ponzi schemes, functioning as both emotional sustenance and cognitive blinder.

THE PONZI PSYCHOLOGY

In Nigeria’s challenging economic landscape, where conventional paths to prosperity have narrowed considerably, hope goes beyond mere wishful thinking, and must be adopted as a psychological necessity for maintaining any sort of mental balance. When people cannot envision pathways to improve their circumstances through conventional means, the alternative options, no matter how risky must become psychologically essential, explaining why many victims have continued to invest in spite of intellectual doubts.

This cognitive dissonance plays a crucial role in sustaining investor participation even as warning signs accumulated. When presented with information contradicting their investment decision — such as warnings from financial regulators or skeptical family members — many investors may experience psychological discomfort from holding conflicting beliefs. Rather than reconsidering their position, most will choose to resolve this dissonance by particularly seeking out information that confirms their choice while dismissing any contradictory evidence.

Risk-taking behaviour among Ponzi investors operate through specific psychological mechanisms that override rational assessment. Research in behavioural economics identifies a phenomenon called “prospect theory” formulated in 1979 by scholars, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. In this theory, it is asserted that “people become significantly more risk-seeking when facing losses or financial pressure than when experiencing stability.” The ongoing economic hardship in Nigeria has created precisely the conditions where risk aversion diminishes dramatically.

Social validation mechanisms significantly amplified individual risk tolerance through psychological contagion effects. Humans are fundamentally social creatures who calibrate their perception of reality through collective consensus. When victims witness friends, family members, and respected community figures participating in and apparently profiting from CBEX, a powerful psychological override of personal scepticism can occur.

FRAUD OR INVESTMENT?

Following the brouhaha arising from CBEX shutting down, many people have come out to decry all forms of platforms for business trading. Udoji noted that there’s a poignant distinction between fraudulent Ponzi models and legitimate crypto investments that a lot of individuals seem to miss. According to him, “they are two entirely different concepts. One operates strictly on transparent and verifiable methodologies. The other one relies on unsustainable economics where early investors are paid using capital from new investors. With Ponzi schemes, there is no tangible activity involved for generating revenue legitimately. It’s just a giant smokescreen,”

“There’s no real underlying value in any Ponzi model. However, cryptocurrency investments have clear sources of revenue which can be traced to transaction fees and appreciation based on increased adoption and utility. You can’t point to any clear source of revenue in Ponzi models. The only thing you can use to compare crypto trading with Ponzi is the element of luck. Luck plays a role in both of them but in different ways. In genuine crypto markets, there’s a lot of volatility because of dramatic swings in the price of assets based on new laws and regulations, new technology etc. The critical difference is that legitimate crypto volatility represents market risk around assets with intrinsic value potential, while Ponzi ‘luck’ is just a zero-sum game redistributing wealth from later to earlier investors,”

“Fraudulent business like CBEX love using cryptocurrency terminology to exploit the technical complexity and novelty of blockchain technology, and deceive people into thinking they are legitimate. They will use known crypto terms like ‘mining’ and ‘staking’. People who are not informed will obviously be bamboozled. They are like parasites, feeding off the success of legitimate cryptocurrency businesses and using it to prop up their resume. People who are not financially illiterate will keep falling for it. Be careful of any business that relies solely on recruiting new investors. Where does their revenue truly come from? Are they just siphoning money from new investors and giving to the old ones? These are the important questions people should be asking.”

WHY PONZI SCHEMES CONTINUE TO THRIVE

As CBEX victims continue to lick their wounds, one is left to wonder how many more repeated failures and widespread warnings need to be given to Nigerians before the hint is taken. When conventional economic avenues fail to provide adequate living standards, the allure of schemes promising 10% monthly returns becomes nearly irresistible to many Nigerians struggling to make ends meet, creating a fertile breeding ground where hope often overrides caution.

It is probably necessary to point out that Nigeria’s strong communal ties and social networks act as vectors for both legitimate businesses and fraudulent schemes. When respected community members, celebrities, social media influencers, or family members vouch for an investment opportunity, social trust often supersedes critical analysis. Additionally, Nigeria’s culture celebrates and respects visible wealth and success, creating immense social pressure to achieve financial prosperity. This cultural context makes Ponzi schemes, which offer shortcuts to visible prosperity, particularly effective at recruiting new participants despite repeated collapses of similar models.

The regulatory environment in Nigeria has historically struggled to keep pace with sophisticated financial frauds. While authorities have made significant strides in recent years, enforcement remains challenging due to resource limitations and the rapid evolution of schemes.

Fraudsters exploit this gap by quickly adapting their models whenever authorities crack down on specific structures. When one scheme collapses, operators often rebrand with slightly modified approaches but the same underlying Ponzi mechanics, targeting those who lost money in previous schemes with promises of recovery. Limited financial literacy education in schools and communities means that each new generation remains vulnerable to these ever-evolving tactics.

The psychological dimension cannot be overlooked in understanding the persistence of these schemes. The human tendency toward optimism bias remains powerful even when previous schemes have collapsed. Popular quote among potential victims is “it will not happen to me”, “It’s better to just try than do nothing” etc. Many participants believe they can time their entry and exit perfectly, beating the inevitable collapse. Furthermore, cognitive dissonance leads many victims to defend schemes even as red flags emerge, as acknowledging the fraud would mean accepting significant financial and social losses. Successful participants from early phases also serve as powerful testimonials, their visible wealth offering seemingly incontrovertible evidence that the impossible returns are legitimate.

Breaking this cycle requires a multifaceted approach that addresses all contributing factors simultaneously. Stronger regulatory enforcement must be paired with widespread financial literacy education that builds critical evaluation skills. Economic policies that create legitimate investment opportunities with reasonable returns could redirect capital from fraudulent schemes to productive enterprises. Media campaigns highlighting not just the failures but the mechanisms of these schemes might help inoculate vulnerable populations against sophisticated pitches. Most importantly, cultural conversations about wealth, success, and community responsibility need to evolve to reduce the social incentives that drive participation. Until these interventions reach critical mass, the cycle of hope, investment, collapse, and renewal of Ponzi schemes in Nigeria will likely continue, leaving economic devastation in its wake.

It is not clear whether the downfall of CBEX, will fundamentally alter the approach many Nigerians take towards investments in the short term. While the immediate aftermath will undoubtedly leave many investors wary and vocal about their losses, the underlying conditions that fuel participation in such schemes such as deep-seated economic hardship and desire for quick financial upliftment, will likely persist. The lure of high, rapid returns often overshadows cautionary tales, especially when amplified by persuasive marketing and social validation within communities.

However, one crucial takeaway from the CBEX saga is the glaring need for enhanced financial literacy and more robust regulatory oversight. The narrative this far underscores how a lack of understanding regarding sustainable investment returns and the mechanics of financial markets makes individuals more susceptible to the deceptive promises of Ponzi schemes.

Simultaneously, the absence of stringent regulation has allowed CBEX to operate unchecked, highlighting a critical gap that needs to be addressed to protect potential investors. Educational initiatives, coupled with proactive regulatory measures and effective enforcement, are essential to build a more informed and resilient investment landscape in Nigeria.

The cultural emphasis on visible success and the social pressure to achieve rapid financial prosperity can inadvertently create an environment where risky ventures are seen as necessary shortcuts. Individual responsibility plays a significant role, but collective effort involving educational institutions, community leaders, and government bodies is equally needed to foster a culture of informed and cautious investing.

The lessons from CBEX’s demise should serve as a painful yet necessary reminder of the importance of due diligence, realistic expectations, and a fundamental understanding of financial principles in navigating the complexities of the modern economy.